By Justin Lafreniere

What an editor should do is often the subject of debate and disagreement. It is a role that changes based on era, economics, the size of the press, or the individual personality of the author or the editor. Editing requires teamwork and cooperation, but what makes an editor talented, successful, or effective for an author? There isn’t a single right way to be an editor, but developing an editorial identity takes time and opportunity, both of which we strive to provide at Stillhouse Press.

Once the author has signed his or her contract, our Editor-in-Chief selects an editorial team for the book, choosing experienced staff who would best fit the project. Each team is made up of two or three Editorial Assistants and a Managing Editor. Usually, Managing Editors are in their second or third year of the MFA program and have worked as Editorial Assistants on other books. It is not uncommon for staff members to speak up for projects they are interested in developing when they encounter them as readers. As a teaching press, we encourage staff members to work on projects that excite them and have found that the editor/author relationship progresses smoothest when both parties are passionate about the project.

Managing Editors and Editorial Assistants meet to discuss future projects.

The Editorial Assistants (usually MFA or BFA candidates) assist the Managing Editor in performing two or three editorial passes on each manuscript. The first is for developmental improvements and to alleviate points of confusion, the second for organization and structure, and the third for line-level concerns. This process varies from editor to editor as manuscripts come to us at various levels of publication readiness, and some require more work than others. All of these comments are sent to the Managing Editor, who filters through them, adds remarks, and passes the suggestions along to the author.

At Stillhouse Press, we believe that a successful editorial relationship hinges on two things: editorial identity and respect for the author and his or her project. An editor must come to a book not as a writer, but as a collaborator with the author. Every writer is an editor in some capacity, but becoming a Managing Editor means abandoning personal stylistic quips and writing biases and embracing the author’s voice and project. MFA students, who are still smack-dab in the middle of their program and their most intensive workshop experience, have the added challenge of recognizing the influence of the pervasive workshop mentality. When editing in workshops, writers provide feedback and give authors suggestions for revision, but these suggestions are given in a theoretical mode.

Editing in a publishing house does not have that nicety. Sometimes things must be done. But other times, things that an author composes must be left to stand on their own. People wearing that double-hat of MFA student and editor must be aware of which is dominant when they discuss their editorial projects. Workshops are prescriptive. It’s the subtext to the name: a manuscript is only brought to a workshop if it needs fixing. Editorial relationships are not like that. So much more must be going right for it to come into an editor’s hands. Even if it isn’t a book that an editor finds exciting, he or she must be able to look at it from the perspective of the imagined reader, not from the standpoint of a fellow writer or even as a craft-oriented MFA student. Editorial relationships that are the strongest are built on a positive notion: “This is already good.”

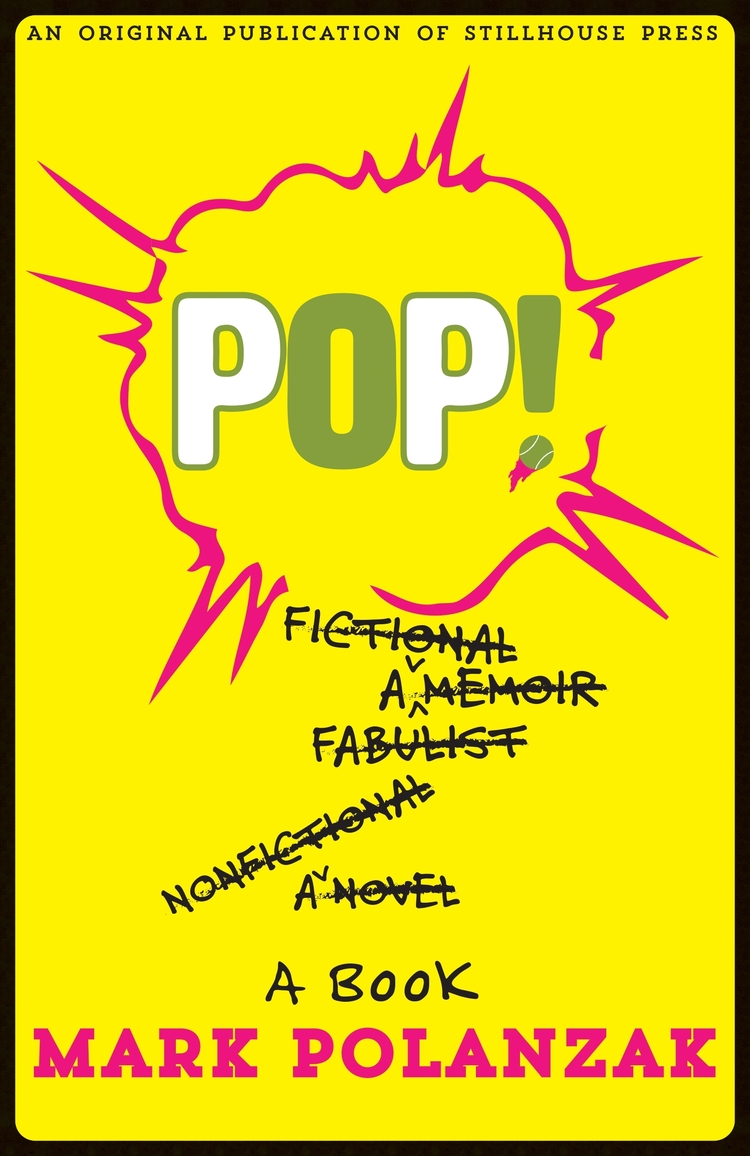

Respecting the author and the project may seem like a no-brainer, but this fundamental component of the editor/author relationship has the most far-reaching consequences of all. One of the most difficult things as an editor is knowing when and how to suggest large changes to a manuscript: the presence of a character, the deletion or rearrangement of scenes, or large-scale structural or organizational changes. This is where respecting the project comes into play. Our memoir POP! was experimental, and in any experimental work, there are going to be conversations on structure. But that book knew what it wanted to be from the outset; it was just a matter of making sure each chapter or section lined up with that vision. When we discussed our first round of comments with Mark Polanzak, we learned that acquisition editors from other houses had resisted the book’s hybrid identity, which is what we loved most about it. At Stillhouse, we have many conversations with our authors to discover their vision for their work before we even begin the editorial process to get a sense of the project from the author’s perspective. We strive to present the best versions of their stories, to help them become the best books they can be, and the only way to do that is with respect for authorial vision.

There is no right way to edit, but there are certainly wrong ways. Stillhouse strives to build a constructive relationship with our authors and their projects, one where the author is always free to reject or resist our suggestions. Our team structure allows for multiple voices and points of view on what’s working or not working in a manuscript, which ultimately means a more thorough reader’s perspective. Our Managing Editors distill that information and keep an open dialogue with authors from first read to final draft. We’ve found in many instances that authors and editors continue to stay in touch even after the journey has finished and the book is in print. There's no better indicator of a successful working relationship than that.

Justin Lafreniere is the Prose Editor at Stillhouse Press and worked as the Assistant Managing Editor for POP! (Mark Polanzak, March 2016) and the Managing Editor for Maybe Mermaids & Robots are Lonely: Stories (Matthew Fogarty, September 2016). He graduated with an MFA in fiction from George Mason University in 2016, where he also served as the Fiction Editor for So to Speak, GMU's feminist literary journal. His work has appeared in Charlotte Viewpoint, The Western Online, and Frostwriting.